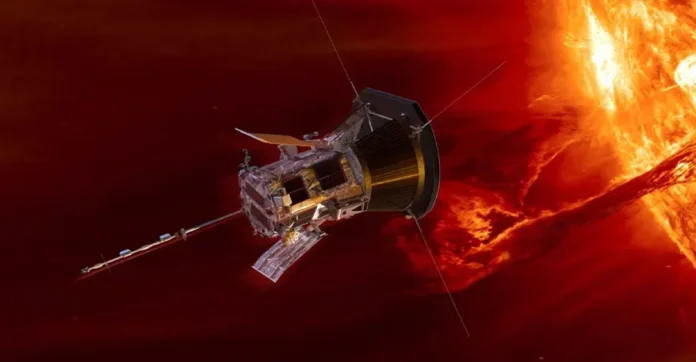

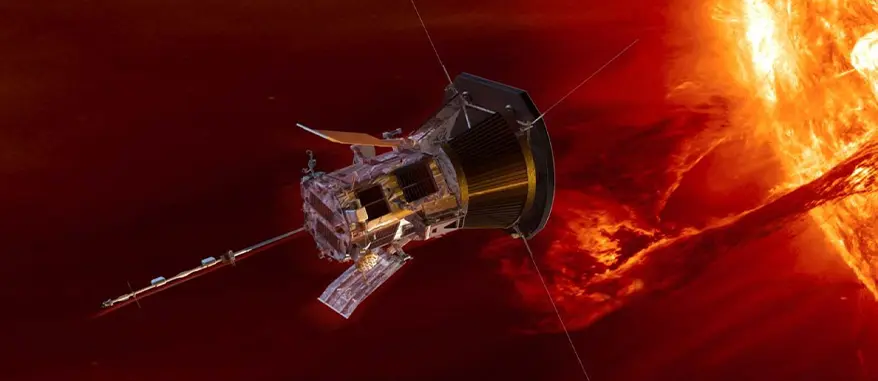

NASA’s pioneering Parker Solar Probe made history on Tuesday, flying closer to the Sun than any other spacecraft in history. During this groundbreaking event, the spacecraft’s heat shield was exposed to temperatures exceeding 1,700 degrees Fahrenheit (930 degrees Celsius), as it ventured into uncharted territory. Launched in August 2018, the Parker Solar Probe is on a seven-year mission to advance our understanding of the Sun and to help forecast space-weather events that have the potential to impact life on Earth.

The spacecraft’s closest approach to the Sun, known as perihelion, occurred at precisely 6:53 a.m. (1153 GMT) on Tuesday. However, mission scientists will not receive confirmation of this achievement until Friday, as the spacecraft temporarily loses contact with Earth due to its proximity to the Sun. NASA official Nicky Fox shared her excitement on social media, stating, “Right now, Parker Solar Probe is flying closer to a star than anything has ever been before,” as it reached a distance of 3.8 million miles (6.1 million kilometers) from the Sun.

To put this remarkable distance into perspective, Fox compared it to the length of an American football field. If the distance from Earth to the Sun was the length of the field, the spacecraft would have been approximately four yards (meters) from the end zone at the time of closest approach. “This is one example of NASA’s bold missions, doing something that no one else has ever done before to answer long-standing questions about our universe,” said Arik Posner, program scientist for the Parker Solar Probe, in a statement.

The spacecraft’s impressive design includes a heat shield that keeps its internal instruments at a comfortable room temperature of about 85°F (29°C) despite the extreme heat of the Sun’s outer atmosphere, known as the corona. The Parker Solar Probe will continue its mission at an astonishing speed of around 430,000 miles per hour (690,000 kilometers per hour). This blistering pace is fast enough to travel from Washington, D.C. to Tokyo, Japan in under a minute.

Mission operations manager Nick Pinkine at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory expressed excitement about the data that the probe will return, saying, “Parker will truly be returning data from uncharted territory. We’re excited to hear back from the spacecraft when it swings back around the Sun.”

The Parker Solar Probe’s mission is helping scientists unravel some of the Sun’s greatest mysteries, including the origins of solar wind, the reasons why the corona is hotter than the Sun’s surface, and how coronal mass ejections are formed. These massive clouds of plasma, which are propelled through space, can significantly affect space weather and even impact technological systems on Earth.

The Christmas Eve flyby is the first of three close passes planned for the mission, with the next two scheduled for March 22 and June 19, 2025. Each of these flybys will bring the spacecraft back to a similarly close distance to the Sun, furthering our understanding of the Sun’s complex dynamics and its influence on the solar system.